In 2024 French publishing house Maison ONA began releasing the backcatalogue of Bernard Parmegiani1 (see at the end of this article). All fresh digitizations of the original source material. Already 16 albums have been released through Bandcamp. This is not the first time Parmegiani’s music has been released and re-released. For me, that offers plenty of opportunity to compare the various releases, focusing on one particular work: La Création Du Monde (1982-1984).

La Création Du Monde

Listen to the GRM version of 1986 which was also used in the boxset of 2008.

Listen to the newly remastered version, released by Maison ONA. (headphone use is recommended!!)

Duration

What immediately strikes me is that the durations of the album are different; 72’47” vs 97’18”. That’s massive! Researching this a bit I learn that there have been variations of the work from the start. Parmegiani’s own discography mentions:

La Création du monde, version intégrale (comprenant 3 opus) – 72'47"

Support audio bande magnétique ; triptyque électroacoustique composé de trois opus distincts qualifiés par le compositeur de « période » :

17'36" : Lumière noire, 1ère période, version révisée 1984.

23’11" : Métamorphose du vide, 2e période.

32’ : Signes de vie, 3e période.

Création version intégrale, Cycle acousmatique/GRM, Maison de Radio France, Paris, 14/04/1984. Le CD La Création du Monde, version intégrale a obtenu les Victoires de la Musique en 1990, catégorie Musique Contemporaine.

So there is talk of a revised version but also of a complete (intégrale) version. The CD, however, ís said to be the complete version. But apparently not, because this new Maison ONA version is substantially longer. It’s highly probable that reason for the shortening of the triptych is quite pragmatic: offically a CD can not contain more than 72 minutes of music.

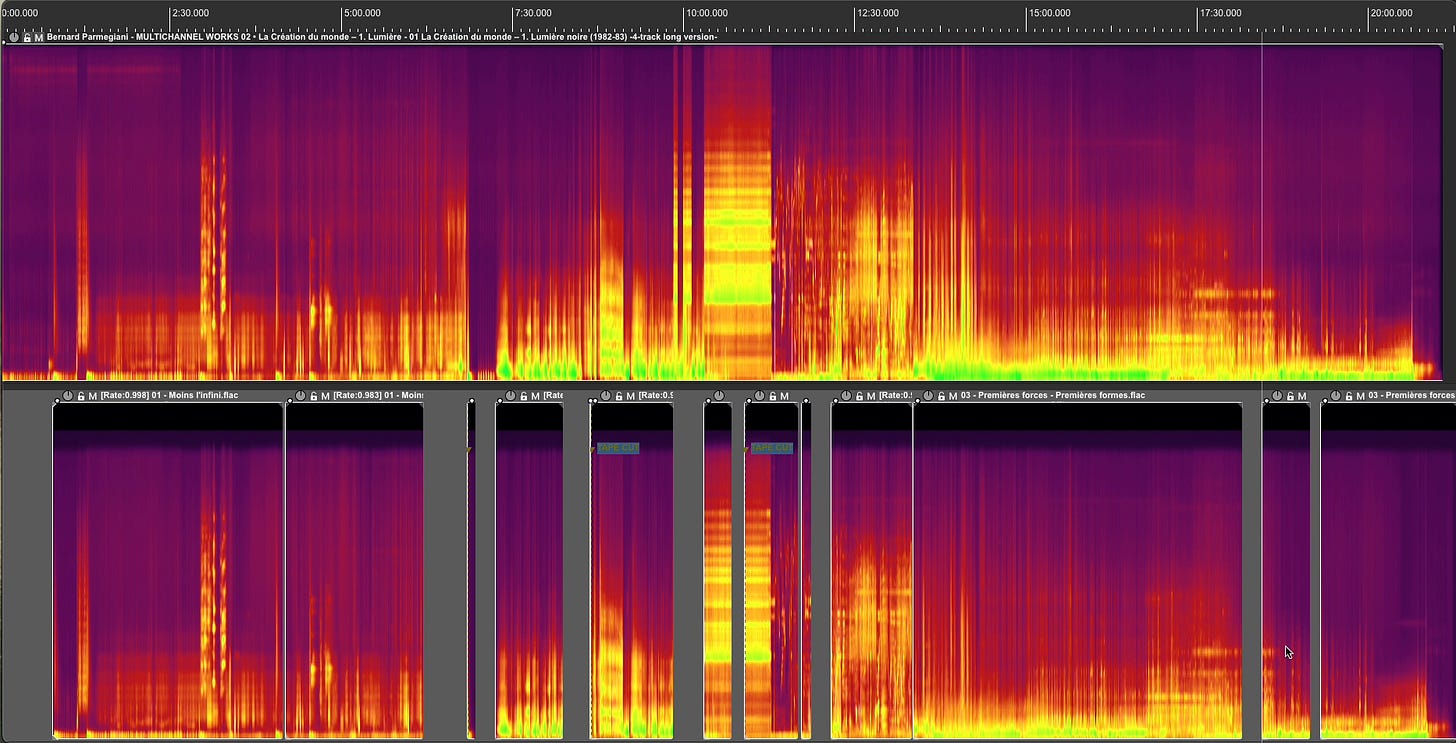

I laid out the two versions of the first part of the triptych (Lumière Noire) to learn more about the difference in duration. Here I have mapped out the two versions; top is the 2025 version, bottom the 1986 version.

As you can see, it’s not so much that Parmegiani simply cut off one particular sequence of the whole work but rather that he made careful decisions about what part to keep and what to take out.

Speed

Another thing that struck me is that there is a slight difference in playback speed between the two versions. The 1986 version is 2% faster than the 2025 version. But it’s not consistent, so I don’t know what happened there. Perhaps a tape calibration thing? And where, in the various processes, did this happen? Maison ONA let me know that the 2025 is completely new digitization from the original tapes.

Binaural

For this 2025 release the original tapes were newly digitized, mixed and mastered. La Création Du Monde was originally designed as a quadrophonic presentation so music on the tapes was on four tracks.

Maison ONA began its work on Parmegiani’s legacy in 2017, starting with scores and graphical archives. About 20,000 documents were digitized

The digitization took place between 2018-2022 at GRM. The original 4 track tape of La Création Du Monde was remixed to binaural instead of the traditional stereo. Additionally, the original four track version is downloadable and can be played back through Dolby Atmos systems.

Because the music was intended to be experienced with the audience in the center and the music coming from four speakers (each in a corner of the room) it makes sense for Maison ONA to make the leap towards a binaural mixdown and master.

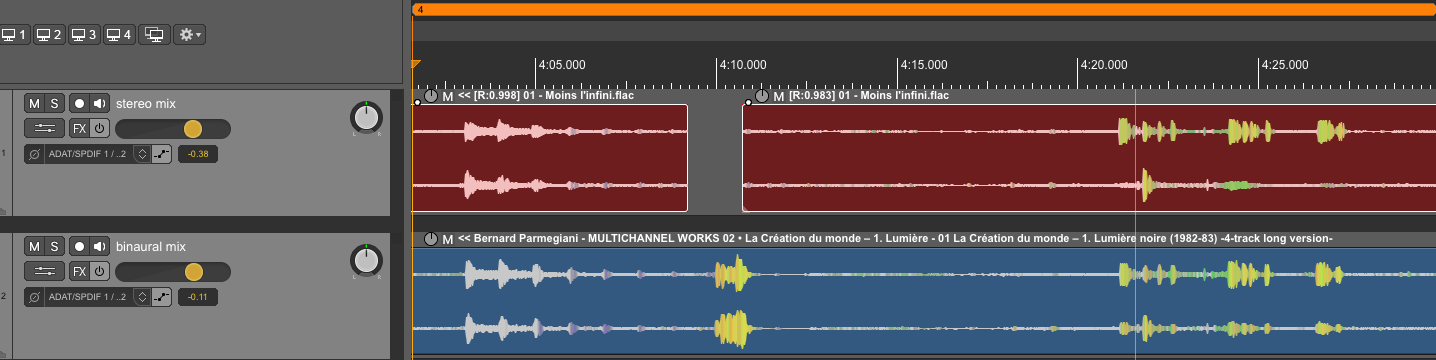

I decided to compare these two versions. Below I focus on a 28 second clip of the first section (4’01” - 4’29” of the 2025 version).

To experience the difference between the two mixes they can best be heard, of course. Below you can listen to both the 1986 stereo version and the new binaural version. You can hear (especially with headphones on) how there is much more separation (‘air’) between the various parts of the work. The stereo version, in comparison, sounds more compressed, and has less ‘depth’ in the sonic field. If you want to listen to these sounds (including the quadro version) in your own DAW, I have a download for you (valid until June 2026).

binaural (2025)

stereo (1986)

Mixing stereo versus binaural

As a 20th century mixing engineer, you were tasked with mixing down a quadrophonic work to two channels, what were the aspects to consider? You would sit down at your mixing desk and close your eyes and imagine what sound coming from what channel was where? You knew channels 1 and 2 were left and right front and 3 and 4 were left and right back.

How to translate this, especially the sounds coming from channels 3 and 4, to a stereo field? You know that sounds coming from the back mostly reach the ears indirectly because your pinnae are ‘in the way’. That translates sonically to a relatively less crispy sound. But does that mean that you should equalize the sound of channels 3 and 4? Also, the sound coming from 3 and 4 would be more dispersed, so that would mean that 3 and 4 are to be mixed a little bit to the middle of the stereo field.

Another strategy would be to fold channels 3 and 4 to the front of the listener but at.a (imaginary) further distance (right side of the schematic). Channels 3 and 4 would have to be played back with lower levels, a bit more to the center and with some additional reverberation.

Whatever choice you make, you add some magic dust to the original sounds in order to do justice to the intention of the composer that the listener experiences 4 sound sources. And still present it as a whole, as a coherent sonic sculpture.

Binaural tech

Enter binaural mixing. Sound research and stronger computer power, especially in the past few decades, have resulted in the development of complex algorithms that are able to simulate the balance of direct sound and the multitude of reflections of whaever imaginary room you can think of. Mixing engineersmake use of software that enables them to experience the acoustics of, let’s say, Abbey Road studios and bring those acoustics into the mix. This way the mixing engineer is able to bring a binaural mix where the various instruments, or in the case of electronic music, the various channels can be experienced much better independently. The listener is better able to concentrate on one particular part of the music.

A major criticism on binaural sounds is that the 3D aspect of the sound disappoints and that on a stereo monitor setup (not headphone) the experience is actually worse. I think this is much dependent on two factors: first, don’t expect too much. It’s not 100% immersive, but a lot more than a good stereo mix delivers. Second, it’s still dependent on a good mixing/mastering engineer. Just as is the case with ‘traditional’ mixing this engineer should check the result of his mix on multiple systems, not just a headphone.

Quadrophony

The idea when ONA started the project (in collaboration with Claude-Anne Parmegiani and the composer’s technical assistant, Marco Marini) was to be “as close as possible” to the original listening experience. Because people mostly use headphones it made sense to apply not only the traditional stereo formats for mastering but also the digital platforms. In the quadrophonic version all choices and technical operations are directly organized by Parmegiani.

Conclusion

Maison ONA has been very thorough in their approach. Being a publisher, originally, of scores (on paper) they have expanded their terrain to special publications and online publication of music.

Electronic music is best experienced in a multichannel environment. Everyone who has ever attended a multichannel electronic music presentation before knows this.

Unfortunately, 20th century labels who wanted to publish had to collapse those multiple channels to a stereo format. At the time that was all there was and mixing engineers made the best of it. Deciding to go back to the 4-channel source and take it from there is the best possible option when (like Maison ONA) you have decided to work towards a presentation that meets contemporary consumer audience formats. By publishing the music in binaural, not just stereo, Maison ONA shows that they are not afraid to make bold choices. And offering the original 4 channel mix in a format (ADM-BWF) that is compatible with contemporary equipment is a clever move.

I hope more binaural and quadro or even octophonic releases by other elecrtonic composers will follow.

Maison ONA website

Bernard Parmegiani’s reworks online

Bernard Parmegiani

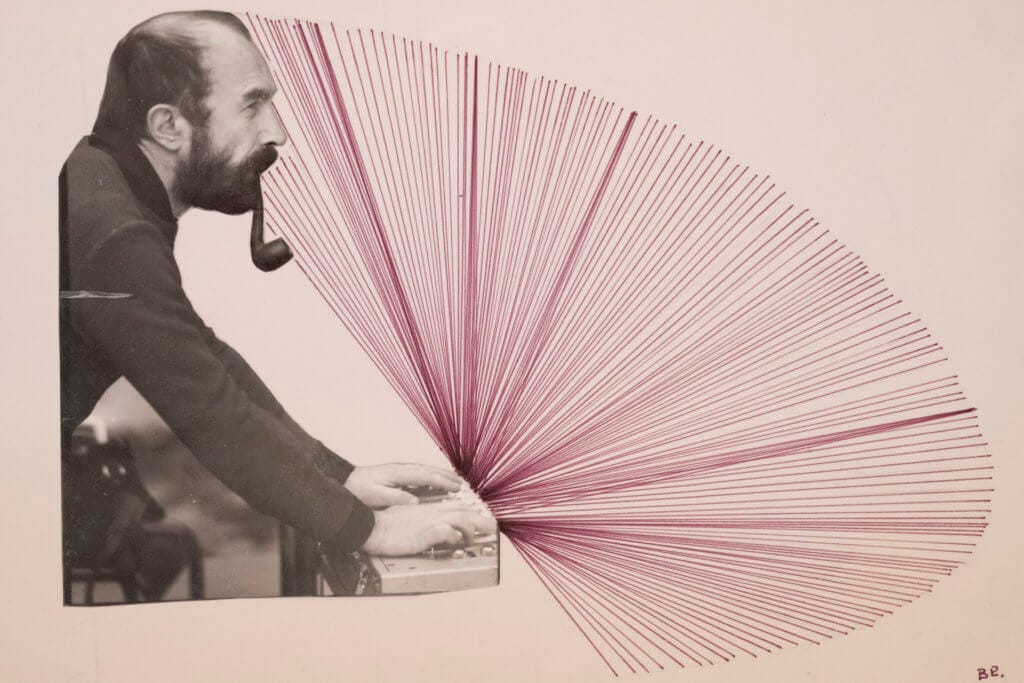

Raised amidst two pianos, Bernard Parmegiani grew up under the Sign of Sound, listening to the everyday scales practised by his mother, a teacher, and to the virtuoso repertoire of his step-father.

He was taken on as a sound man first on the radio and later on TV, which is where he conducted his first experiments with "bit twiddling" on tape. During this time he was also studying mime with Marcel Decroux and later at Jacques Lecoq's theatre school, which gave him an awareness of the plasticity of space, a lesson that he would draw on in his later compositions and in the architecture of his sound universe.

Then he met Pierre Schaeffer who encouraged him to attend a training course in electro-acoustic music ( 1959) and shortly after he joined the Groupe de Recherches Musicales ( 1960), of which he was to remain a full member right up until 1992.

Pierre Schaeffer put Bernard Parmegiani in charge of the Music/Image unit of the ORTF's Resear'ch Departement, where he went on the compose the music for both full-length and short films made by the likes of Robert Lapoujade, Peter Foldés, Piotr Kamler, Valerian Borowczyck, Pierre Kast, 1acques Baratier et Peter Kassovitz amongst others. The proved to be a first class training ground for learning how to deal with the problems of musical form as these relate to time, and how to overcome the constraints imposed by the medium of the cinema. It was here that he learned to exercise his freedom of creation, albeit within the framework of having to respect the time for which an image was displayed on the screen and having to reflect the contents of films of which he was not the author. He also wrote the music for several jingles ( for France Inter and Roissy Airport and so ...) and others advertisements, as well as songs and music written for television, the ballet.or the theater All of this was good practice, and it later encouraged him to create pieces of music that, when the sound was heard within the context of the stage setting would become the occasion for the humorous or dramatic game.

In 1964, he composed Violostries, his first work for the concert hall ( music for tape and violin), first performed at the Royan Festival by the violonist Devy Erlih.

There then followed 40 years of uninterrumpted research and musical creations built out of an ongoing fight that led him to regard bodies of sound as living bodies. He took a keen interest in those areas in which the improvisation techniques used by jazz musicians mett with electro-acoustic music, working with Jean- Louis Chautemps and Bernad Vitet along the way: Jazze; xtoday, Parmegiani's own output, primarily made up of sounds recordes on tape, includes moore than 70 pieces of concert..

His long association and familiarity with the moving image led to his developing a keen interest in video art and he made three music videos : L'œil Ecoute ( 1973), l'Ecran transparent et Jeux d'artifice ( 1979).

Except some mixed pièces, his work as a whole take the form of music for « fixed sound », coming within the scope of the large repertoire of electro-acoustic music.

Among the catalogue of works by Bernard Parmegiani works for concert), some of the titles testify more particularly to his musical path : Violostries (1965), Capture éphémère (1968), l'Enfer, after The Divine Comedy from Dante (1972), Pour en finir avec le pouvoir d'Orphée (1971-1972), De natura sonorum (1974-1975), La création du monde (1982-1984), cycle Plain temps ( 1991-1993), Sonare (1996), La Mémoire des sons (2000-2001), Espèces d'espace (2002-2003) Au gré du souffle s'envole le son ( 2006). (source: brahms.ircam.fr)